Pleasures of 2015

by Carrie Devall

I spent a lot of time this year learning basic Russian and Finnish, and reading cheesy horror and thrillers in Spanish and French to work on vocabulary and fluency. Not very exciting, eh? However, I have to recommend the FinnishPod101 videos on YouTube if you want to learn a few basic phrases before heading to Helsinki in 2017. They are well made, easy to follow, and let you see and hear the words at the same time.

Reading in English, I ended up focusing on Finnish, Estonian, and Scandinavian fiction in translation. Most of the Scandinavian fiction in the Hennepin County library system leans toward the more violent and callous end of crime/noir. Leena Leihtolainen’s The Bodyguard was the standout here because it did not glorify violence, had a female heroine who was extremely self-reliant but mostly plausible, and dipped into Finnish politics a bit. The lynx theme did not hurt, either.

The Howling Miller by Arto Paasilinna is a 1981 novel that got some mixed reviews because it was translated into English from a French translation. I found it to be funny, touching and thought-provoking. It’s a picaresque novel and social satire with a deceptively simple style that reads a lot like many novels based on fairy tales. It also has some fantastical twists. The Howling Miller makes fun of the stoic self-reliant ethic and hypocritical romance of wilderness that characterizes both Finnish and upper Midwestern U.S. culture, as well as inhumane bureaucracies and the stifling aspect of small communities.

The Blue Fox, by Icelandic writer Sjón, is a very short novel about hunting in winter but has a poetic style and, again, some nice fantastical twists. I started but have not finished the Icelandic science fiction novel LoveStar, by Andri Snær Magnason, but the opening chapters were snazzy, funny, and full of wacky world building. A corporate tech god has unlocked the key to transmitting data via birdwaves, hence the wackiness.

The two novels I read this year that have stayed with me the most were both by Sofi Oksanen, a Finnish-Estonian writer living in Finland. She also made some strong, brave speeches and interviews in 2015 about the Putin regime historical revisionism that her fiction also works against. The two novels I read covered a lot of territory, moving between the periods of successive Russian and German occupations of Estonia and more current eras through stories of families from rural villages.

The older novel, Purge, deals with the Russian sex trade in the present and the many forms of sexual as well as economic exploitation during the occupations. The more recent novel, When the Doves Disappeared, similarly focuses on the things people do to survive the occupations and the long-term effects on their families, their communities, and their selves. In Doves, this includes writing revisionist literature. These are obviously not fluffy books, but I found them incredibly well written and leavened with deep compassion and understanding.

The excellent translator for both Oksanen novels, Seattleite Lola Rogers, also translated the Lehtolainen novel, Antti Tuomainen’s The Healer, and Johanna Sinisalo’s The Blood of Angels, so she is 5 for 5 in making my year-end lists.

Back to the speculative, Mati Unt is seen as one of the most influential modernist and then post-modernist writers in Estonia, and he wrote about werewolves, outer space, electricity, and vampires. Many of his postmodern books were conglomerates of snippets from various sources juxtaposed against one another, as Johanna Sinisalo has done in many of her novels. I read Unt’s Diary of a Blood Donor, which was clever and witty but gave me the feeling I was missing a lot. Doing a little more research, apparently Unt was somewhat blasphemously homaging Lydia Koidula (1843-1886), who is seen as the first female Estonian poet and the first poet to express an Estonian longing for independence, in a Gothic vampire novel. This goes on my research and reread list.

The movie that sent me in pursuit of Estonian literature was the funny 2010 documentary “Disco and Atomic War,” by Jaak Kilmi, which focused on the influence of Finnish TV, Dallas and disco on Estonian culture during the 80s. The documentary visually depicts how Estonians watched Finnish TV en masse from behind the Iron Curtain with illegally modified TV sets. This began to unravel Soviet ideological control despite attempts to block the broadcasts and create state-approved disco shows.

The Minneapolis St. Paul International Film Festival (MSPIFF) had a good catalog this year. I got to see the Lithuanian lesbian movie Sangailės vasara (The Summer of Sangailė), which had good production quality, great acting, and an okay story. Chagall/ Malevich was a fascinating look at Marc Chagall’s early life, his amazing wife, and the different artistic paths taken by Chagall, the Jewish dreamer trying to float above anti-Semitic, Soviet-controlled Byelorussia, and his opposite, Kazimir Malevich, the father of Suprematism (the artistic movement reflected in many of those old Soviet propaganda posters.) The Russian Woodpecker is a quirky and deeply disturbing documentary about the Chernobyl disaster and the role that U.S.-Soviet jockeying for military supremacy may have played in triggering the blast.

We got the last tickets to the Finnish movie, Mielensäpahoittaja (The Grump), by Dome Karukoski. It was sold out for good reason. An elderly stoic and “self-reliant” farmer coming to visit his citified children in Helsinki and the ensuing culture clash is as Minnesotan a story as it is Finnish. The movie was very tight, well paced and full of visual contrasts and deadpan acting that made the over-the-top actions funnier.

Bande de Filles (Girlhood) by Céline Sciamma, is focused on teenaged French girls in a banlieue/suburb outside Paris struggling to find their way through the obstacle course created by racism, sexism, and ties to family and tradition. It was similarly well constructed, focused on the characters and their personality quirks, and funny and moving in turns. Good music and visual style also made the package work. It is now available on Netflix, as is my last year’s teen girl movie pick, We Are the Best.

Stanley Nelson’s documentary The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution contained an immense amount of video footage collected from all over the world showing the day-to-day interactions of members as well as the public actions. It underscored how women were integral to the organizing as well as all the well-known male leaders.

I also found the Pussy Riot documentary, available on Netflix, quite interesting, even after having read Masha Gessen’s lengthy book about the Russian feminist activist performance art group/punk band. The documentary includes footage of their court trial, some of their performances, and interviews with people ranging from family members to the patriarchs of the Russian Orthodox Church.

In terms of nonfiction, Finding the Movement: Sexuality, Contested Space, and Feminist Activism, Duke U. Press, 2007, by Finn Enke (book published under Anne Enke), asks interesting questions about how histories of the women’s movement are constructed and how participation is characterized to define social movements as exclusive rather than broad and diverse. This book documents the participation of a wide variety of women in community organizations such as battered women’s shelters and softball leagues in the Midwest to explore these questions, with a focus on women’s contestation of public spaces.

I spent some time rereading Barbara Deming’s writings about her participation in the Civil Rights and peace movements in the 50s and 60s and the Seneca Women’s Peace Encampment in the 80s, particularly Prisons That Cannot Hold. She is a powerful theorist of non-violence from a non-religious basis. I was directly influenced by her ideas through SWPC members I did direct action with in the 80s, and it was interesting to read her work more thoroughly 25 years later.

This was accompanied by A Saving Remnant: The Radical Lives of Barbara Deming and David McReynolds, the 2011 dual biography from Martin Duberman. I have really enjoyed Duberman’s recent double biographies of queer activities and/or artists. Deming and McReynolds were both involved in the peace movement, the Civil Rights movement, and early gay activism, but in very different ways and with a crucial difference being Deming’s trajectory towards lesbian feminist peace activism.A Saving Remnant is a little more draggy than the double biography I read last year, about Essex Hemphill and Michael Callen. However, it relates in detail some crucial pieces of movement histories, such as the internal debates and the coalition work by particular individuals, which are otherwise quickly becoming lost to time and the ever-expanding internets.

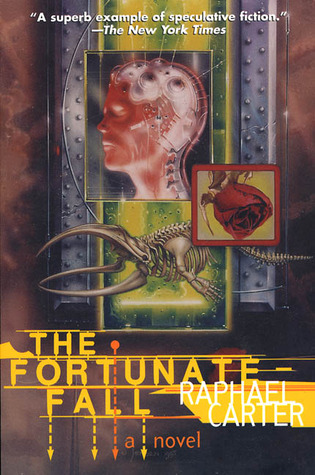

Last but not at all least, I just finished The Fortunate Fall, by Rafael Carter, a very complicated (post-) cyberpunk novel from the late 1990s, which I somehow never got around to reading before, despite queer cyberpunk. Yes, I am slapping my head, hard, though only virtually. So many things come together in this novel, with a critique of pretty much everything you can think of that fits in 21st century science fiction sandwiched in between plot points but also a wicked sense of humor. It still packs a very strong punch. Its future Russia is all too plausible, not the easiest feat of prognostication in the late 1990s. I join the long line of people asking, Why is this book not in print?

Carrie Devall writes from Minneapolis, MN, where it rains a lot thanks to global warming.

1 comment:

Thanks for this interesting post and your generous comments about my translations. I did not translate Leena Lehtolainen's The Bodyguard, however. That was translated by my colleague and fellow Seattleite Jenni Salmi.

Post a Comment